As previously discussed, the test boards themselves will have to be assembled together in order to form a closed loop of track to be used, then disassembled when done to clear up space.

When I really started thinking on how I would go about actually building the boards - around May this year - I didn't have a clear idea on how to go about it - neither connectors, structure, not even the material to be used. In fact even the material that was used as base for the existing layout is something that was bought by my dad since I was a kid. And 1980s in the country I grew up in - Romania - meant that communism won't really allow a large set of choices when it came down to wooden boards (the same limited set of choices were around the scarce quantity of food, too). So we ended up with some sort of MDF purchased one evening and carried across town by public bus. But fast forward to today, and being part of the civilized world means pretty much being able to get whatever you want, since there will be a retailer out there that sells it. What was left to do was go documenting on the Internet, which was bound to yield what the model railroading world deemed the best solution for what I was looking for.

It turns out there are 2 clubs - FREMO in Europe and FREE-MO in US - that built their own comprehensive standard about modules for model railroading. A full PDF for the former can be found on this page, and for the latter here. Studying both gives plenty of data regarding which materials to use, how the end plates for the modules should look like (complete with drawings and dimensions), height of modules, ways of securing the modules together, event paint to be used.

Let's start - for the material it's important to avoid dimensional lumber. This will warp in time. Instead plywood should be used, given the successive layers of wood fibers placed perpendicular to each. FREE-MO even goes as far as explicitly name birch plywood as the material of choice. Problem solved here.

For the module's underlying framework itself, neither standard goes into great detail. I couldn't find much aside from how the end plates should look like. Nothing like L-girder or other type of detail. Turning to other sources - Miniatur Wunderland did document their initial process of building the wooden framework, yet their exhibition is permanent, so not very much that could be used from there. Others, such as Mianne Benchwork, go into details (given they're selling the end product), but their method of connecting everything together is by cam lock and nut - which my initial tests didn't really indicate that the best thing for my needs. At this time I don't have a final picture of how the test boards will look like, but I'm getting closer.

Another aspect is connecting the boards together. The FREMO standard mentions only using 8mm bolts to secure the boards together (inserted through 12mm holes), yet there's no precise instruction for what to use to align the boards. Half a millimeter misalignment at this scale means a big problem. More searching led to Vikas Chander's blog, that has a post handling building FREMO modules. In this post, he's showing the connectors used, and a link to the supplier that sourced it for him. Unfortunately the link is currently dead, but I managed to find a source for those exact things here, at rbs-modellbau. Went ahead and got 3 pairs of them in September, at about 8 EURs per pair. I continued my search for other types of connectors, and came across pattern makers dowels. An online shop that has them is railroomelectronics - the direct link is here. A pack of 2 pairs of these costs about 9 EUR, coming in at 4.5 EUR per pair. I've also ordered 2 packs in September. I also came across table-top alignment pins (a link here) but from what I understood they're less precise than the former 2 types above. I stopped here, and decided that the end goal is to analyze both types of connectors and choose the best.

That's pretty much all the info I needed to go ahead and do a proof-of-concept consisting of 2 tiny modules, that could be connected and disconnected. I already had a board of 1x1 metres of 1.5mm thick birch plywood bought in July. For connecting the the various plywood pieces, I settled on using 8mm dowels. All that was left was doing a plan and actually build the thing. I quickly ditched the idea of drawing on paper - there would be a lot of erasing and redrawing involved -, and went ahead and looked for a software tool. On the RBS page that goes into detail about what they use, I saw "Inventor" as the 3D software. I found out it's something Autodesk has been building close to 20 years for now, and from the various Youtube videos, it looked like something I needed. So I learned the basics for Autodesk Inventor, and then eventually designed the mini-test boards/mini-modules.

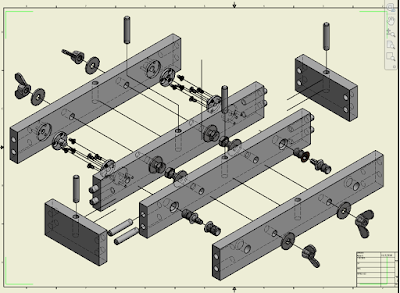

Seen in the picture is the exploded view of the end result. The 2 long pieces in the centre - the ones closest together and the 2 small lateral ones form one mini-board, while the other 2 form another one. These outer 2 in fact form a similar mini-board as the first one, but are depicted here separated, as to highlight the connectors and how they fit together. The 2 mini-boards can thus be connected at will - either using one set of connectors, or the others. Note that the top of the 2 mini-boards is not shown in the diagram, as to not overload the plan. Click on the picture to zoom in.

The connectors seen in the lower right (not the wingnuts on the far right, but those between the 2 long pieces) are the connectors supplied by RBS, while the ones in the top left are the pattern makers dowels ones.

The connectors seen in the lower right (not the wingnuts on the far right, but those between the 2 long pieces) are the connectors supplied by RBS, while the ones in the top left are the pattern makers dowels ones.

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu